By Yanick Rice Lamb

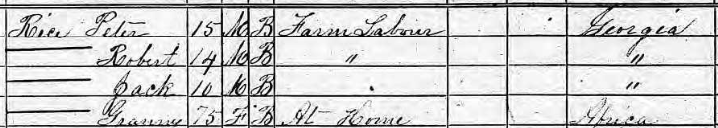

Five-year-old Peter Rice grew up in one of 12 slave houses on land owned by George Lorenzo Dow Rice, M.D., according to the 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedule for Houston County, Georgia. He and his siblings, from baby Jack to 9-year-old Stephen Jr., were under the watchful eyes of their parents, Stephen, also known as “Step,” and Sallie Rice, along with “Granny,” who had survived the Middle Passage from Africa.

In 1860, Houston County had 28 “free colored,” 10,755 slaves and 4,828 white residents. The Rices were among 70 slaves working the plantation of Dr. Rice, sometimes listed in historical records as Dr. G.L.D. Rice or Dr. George L.D. Rice. “Dr. Rice owned 82 slaves in 1864,” our family historian, Sarrah Louise Talbert, wrote in her invaluable 1985 book All Our Children: A History of Our Family.

Some of us have wondered about the people who had an impact on our ancestors in ways we may never know. Here is some cursory background information on slaveholding Rices and McGehees, who owned the property where our ancestors later worked as sharecroppers. It is based on new research as well as Sarrah’s extensive work.

George Lorenzo Dow Rice, M.D.

![“One of the most imposing monuments in the [Marshallville] Cemetery is that of Dr. G.L.D. Rice." (Photo: Macon County Historical Society)](https://peterricefamily.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Marshallville-Cemetary-possible-monument-donated-by-Dr.-GLD-Rice.jpg)

Two decades later, Dr. Rice indicated that he had 22 acres of cotton in a testimonial dated Jan. 26, 1871, for “Guston’s Improved” fertilizer that appeared in Southern Farm and Home magazine. He described his yield as “nearly two good bales of cotton per acre.”

Dr. Rice also had a philanthropic side, donating money for the Marshallville Cemetery in Macon County and the Old Asbury Church “in which three denominations worshiped — the hard-shell Baptists, the Missionary Baptists and the Methodists,” Louise Frederick Hayes said in the “First Towns of Macon County” as noted by the local historical society. “One of the most imposing monuments in the cemetery is that of Dr. G.L.D. Rice, who donated four acres for the construction of a ‘substantial edifice’ for the Baptist church.”

Marshallville’s founders were from Orangeburg, S.C. Dr. Rice was born just southwest of there in tiny Bamberg County, S.C., to Jesse and Sarah (Wroten or Rhoden) Rice on Aug. 16, 1821. It’s possible that Peter Rice’s parents, Steph and Sallie, might also be from Bamberg County, since they along with Dr. Rice’s father ended up leaving South Carolina at some point and living with him.

The 1850 census for Houston County shows 56-year-old Jesse Rice living with his son and Georgia-born daughter-in-law, Frances, 22, in Houston County. Frances Carolina Dunn, Dr. Rice’s first wife, died on July 31, 1857. Two years later around 1859, he married Ophelia Emily Ramsey, “an adopted child by the first wife of Dr. George Rice,” according to Our Multi-National Heritage to Adam, Ancestors of Merlene Hutto Byars, Volume 1.

Early in his second marriage, he joined Levi Ezzell in representing Houston County in the Georgia House of Representatives. On Nov. 9, 1861, he was appointed to the Committee on the Deaf and Dumb Asylum. A few days later, he was granted a leave of absence from the remainder of the session to attend to “urgent business.” The Confederacy and justifications for slavery were prominent topics during these sessions. For example, Gov. Joseph E. Brown claimed that slaves constituted “a dependent class, generally contented and happy.”

To defend the way of life in Confederate states, Dr. Rice fought in the Civil War as part of the 12th Georgia Cavalry (Robinson’s) (State Guards), Company B. He was also an assistant rebel surgeon at the 14-acre war prison in Andersonville, Ga. Writers who criticized prisoner treatment quoted him in their articles and editorials.

An editorial in the Medical and Surgical Reporter cited an Aug. 9, 1864, report to the medical inspector in which Dr. Rice indicated that sanitary conditions might improve “when all the marshy ground is well covered over with sand, which should be done as speedily as possible.” In a medical update a week later on Aug. 17, the New York Times quoted him as saying, “As Officer of the Day for the past 24 hours, I have the honor to report that the filling up of the marsh inside the prison is progressing slowly.”

Dr. Rice died of heart disease on April 6, 1880, in Houston County. He is buried in a family cemetery in Marshallville.

William Felder McGehee

After slavery ended, Peter Rice and his family lived and sharecropped on William Felder McGehee’s plantation in Houston County, as Sarrah has noted. At the time of the 1870 census, Peter was listed as a 15-year-old farm laborer, along with his father, Stephen; older brother, Stephen Jr., 19; and younger brother, Robert, 14.

“In 1870, Stephen Rice owned personal property that had a value of $500, which was a lot of money during that time,” Sarrah said. “Personal property could have been a horse and buggy, cattle, tools and household goods.”

By comparison, McGehee’s personal property was valued at $15,000 with $50,000 in real estate. It’s unknown how fair he was with sharecroppers.

“Descendants of the Rice family lived on McGehee land well into the 1920s,” Sarrah wrote in All Our Children: A History of Our Family.

Born to Edmund and Eliza McGehee around 1841 in Houston County, William Felder McGehee comes from a long line of landowners and slaveholders. His ancestors, who came to New Kent County, Virginia, from Scotland, tended to pass down property to their heirs, including land, livestock and furniture. Some specified that slaves be sold to generate income for descendants.

In 1746, his great-great grandfather, Edward, had 2,830 acres in Amelia County, Virginia. Two years later, he acquired 5,788 more acres. He also participated in the French and Indian War.

The family name has gone through several incarnations. For example, Wlliam McGehee’s great-great-great-great grandfather, who was born around 1618 in Scotland, was known as William MackGahye.

“In the latter half of the 16th century, this branch of the clan led such wild and hunted lives in the misty mountains that they became known as MacEagh or ‘Sons of the Mist,’” one of their family historians said. “It may be that it is from this Gaelic patronym that James MacGregor took the name MacGehee.”

William Felder McGehee died on Nov. 22, 1885, in Houston County. He’s buried at the Evergreen Cemetery in Perry, Ga.

Yanick Rice Lamb, who grew up in Akron, Ohio, is a great-great granddaughter of Peter and Sophie Ingraham Rice. Their son Willie, one of 16 children, was born in February 1884 in Houston County. Willie married Luella Champ or Champion on Dec. 7, 1905. They were the parents of Rudolph Rice, who was born on May 10, 1910, in Fort Valley, Ga., and died on Dec. 19, 1976, in Akron. Rudolph’s son and Yanick’s father, Professor William R. Rice, was also born in Fort Valley, on Sept. 29, 1929. He died on April 26, 2009, in Albany, Ga. Yanick is the mother of Brandon Lamb and grandmother, or Nini, of Santana Lamb.